The FAQ’s that I get the most F – ly about Dying Fall involve the backstory of Brackmor Island. Particularly, were the L’Amaurys real historical figures?

The FAQ’s that I get the most F – ly about Dying Fall involve the backstory of Brackmor Island. Particularly, were the L’Amaurys real historical figures?

Yes, and no. If you haven’t read the book yet, don’t worry — no spoilers. In the book, the ruins of L’Amaury Castle were originally built by a notorious family of pirates who occupied Brackmor Island in the centuries after the Norman conquest of Britain. As Mottley explains to Baker,

“The L’Amaurys were an old Norman family, originally connected with the Montforts. That connection was quietly erased sometime around the death of King John. For nearly a hundred and fifty years, the L’Amaurys controlled this channel and thereby controlled the greatest fleet of merchant vessels in the world. As long as they held this island, no one could touch them, not even the king.”

My real-life inspiration for the setting, Lundy Island, did have a rebellious piratical family in residence from the 12th to 14th centuries: the de Mariscos. However, they have no real-life connection to the historically significant Montforts. The L’Amaury family, which was indeed connected to the Montforts, has no real-life connection to piracy.

Fun, isn’t it?

But who were the Mariscos?

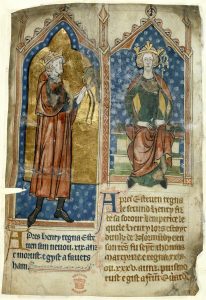

Under the reign of King Stephen, between 1135-1154, Lundy was occupied by an offshoot of the aristocratic Montmorency family, known locally as the de Marisco family. Under the reign of King Henry II, Sir Jordan de Marisco styled himself “Lord of Lundy.” Jordan was the king’s nephew, having married one of Henry’s nieces from the wrong side of the blanket. This doesn’t seem to have done him any good. Henry called shenanigans.

“Having by his turbulent conduct rendered himself obnoxious, his stronghold of Lundy was declared forfeited and granted by Henry to the Knights Templars.”

The Mariscos’ response?

“Come and take it.”

“Come and take it.”

As there is only one safe landing beach, conquering the island by force would be a daunting and costly prospect. The Mariscos took great advantage, and used Lundy with impunity as a base for pirate raids on shipping in the channel and on villages up and down the coast. They were also known to be wreckers and plunderers, deliberately setting lights on the cliffs to lure ships to a violent end on the rocks below.

The family blatantly defied the authority of England in criminality and outright rebellion through the year 1238, when William de Marisco, calling himself “King of Lundy” participated in a plot to murder King Henry III.

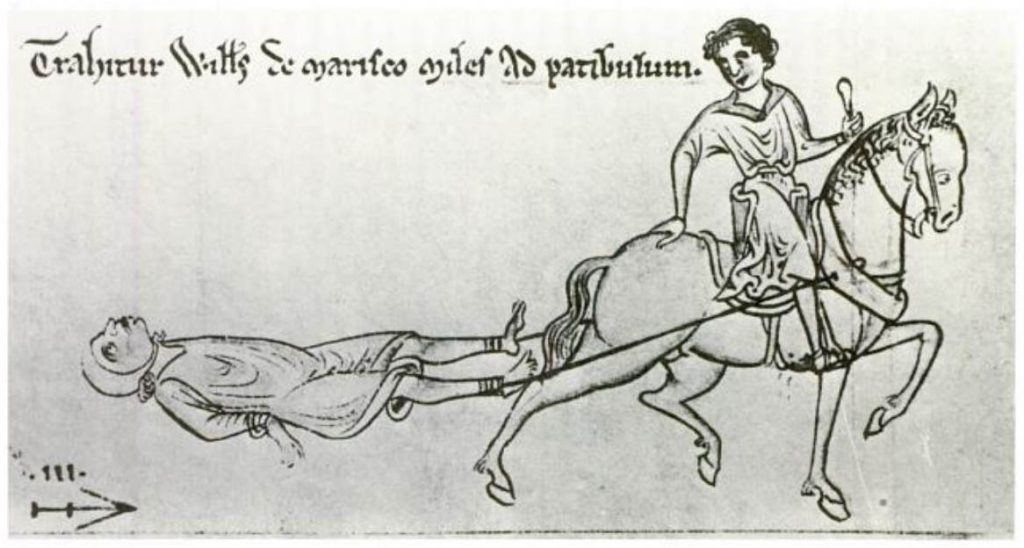

That was the final straw. Henry sent troops in retaliation, who scaled straight up the cliffs, overpowered the pirate-king and his warriors, and took him to London. He was tried, convicted of treason, and given the traitor’s death: hung, drawn and quartered.

Henry III replaced the Mariscos’ fortress with a castle (ironically called Marisco Castle), but neither he nor his successors managed to keep control.

Between the 13th and 18th centuries, Lundy was an open and lawless place, with little connection between its official owners and its actual use. The authorities made several attempts to clean the place up, including granting it to the Cistercian monks. But Lundy was thoroughly incorrigible.

In 1627 a band of privateers from the Barbary coast in the Ottoman Empire occupied Lundy. For five years they terrorized the coasts of England, Wales, and Ireland, capturing villagers and ships’ passengers. Their prisoners were sent to Africa and sold in the slave markets of Tunis and Algiers.

In 1627 a band of privateers from the Barbary coast in the Ottoman Empire occupied Lundy. For five years they terrorized the coasts of England, Wales, and Ireland, capturing villagers and ships’ passengers. Their prisoners were sent to Africa and sold in the slave markets of Tunis and Algiers.

While pirates, smugglers, and shady businessmen continued using Lundy as a convenient hideout for two more centuries, the island fell into decline. A lighthouse was finally built in 1819, but otherwise the nineteenth century saw Lundy as just a worthless, abandoned rock.

Until it became the Kingdom of Heaven.

Next up: William Henry Heaven’s beautification of Lundy, and his influence on Brackmor.

Know any history/mystery buffs who’d enjoy this series? Please share!

Mister Mottley & the Dying Fall is available now in ebook at your favorite retailer, and is coming soon in paperback!